I

t was a feeling I had from the very first time I visited,” he says. “There was something about this place. I just had to come back,” he chuckles… clears his throat, “It reminded me of England’s Lake District, the rolling terrain, deep skies, stacked stone walls and hedgerows, brick, gravel and cobblestone roads. But it was so much more—it felt like home.”

“The history of the town is remarkable,” he says. “I wanted to preserve it, to learn from it,” he pauses. Inside his faraway look, I imagine him thinking about some distant village on a lake in the Scottish Highlands, or the English countryside. “Then it became my sanctuary…” From what I wasn’t sure, but I didn’t ask. “…there was a timelessness, something that called out from a land carved by rivers and streams, the wind—for millions of years. It called to me from the old town too, its succession of human settlement.”

Nancy begins to clear our plates. I look around at the antique furnishings in the elegant dinning room. This room had hosted Mayors, Governors and Cabinet officials—now us. I feel taller here, as if I‘m another person. Unc had accepted us into his world. His world of privilege and adventure. This world I want for my own. A world where everything was in place, where people grew old and rich, and had the power to change people’s lives—to save them.

Dinner with Unc and Pete makes me feel older and wiser, and richer. I see myself in a different light. Throughout the evening, I can feel the anticipation rising within me, the excitement of traveling deeper into the driftless area, and on to an enchanted river. Pete seems excited too, but I want to make sure he’s fully prepared to see the different world we will soon encounter. “Unc, why does the landscape look so different here?” I ask, wanting confirmation of the things I’ve been trying to explain to Pete—things Unc understands better than me.

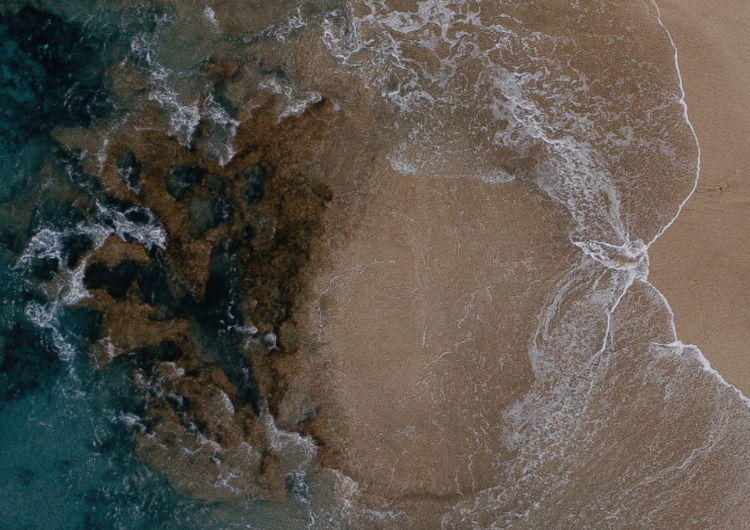

“Ice giants” he says, “glaciers of the last ice age avoided this whole area.” There are different theories too. The region had been called the Paleozoic Plateau, perhaps one of the first portions of land to emerge from a primordial sea, six to seven hundred million years ago. How the lacerated rock base of the headwalls of the driftless-ness, dewatered the lubrication from beneath the glaciers, diverting their paths. “So, here, the erosion progressed in a more typical fashion. What you see today are the remnants of some of the oldest mountains on earth—Wisconsin’s Lost Mountains.”

“Like some lost world right?” And I look right at Pete as I say this—his eyes open wide. This had been one of my selling points for the trip, though it honestly hadn’t taken much. As I looked into Pete’s wide eyes, I wondered about my own reasons. Why was I here? Maybe I hoped to continue my conversation with God—the one that began with John in a coma and ended with his death. God hadn’t said much since then, and if he had, I hadn’t been listening.

As I sit and listen to Unc and Pete converse, my rambling thoughts overpower my concentration. I think about how Galena had faced death, and how its magisterial landscape, part of the driftless area, had been protected as if by the hand of God—did He turn the glaciers away? Part the Red Sea? I recall how the promised land was preserved and delivered and before that, when the Israelites had been spared the angel of death by the blood of spotless lambs painted on their door frames—the first Passover. And this place of abundance and beauty, passed over by powerful glaciers. Perhaps some new Eden?

Maybe I am here to travel back in time. To the time when God and I were still on speaking terms. Had he forsaken me? I needed to find out.

Wallace and Nancy serve dessert and coffee. I awaken from my daydream.

After dessert, I ask for brandy and cigars. Unc laughs. None are delivered. “What time do you want to leave for the river?”

“Early, around 6:00 am. We want to get a good first day in.” I think about how he was good at sending people out on adventures. He had been a hiker and a fisherman, carrying out his wilderness expeditions all over the world. He was almost seventy and still very active. “Thanks for everything Unc! You should join us.”

He chuckles. “Thank you. I have other fish to fry. I’ll see you when you get back.”

***

The morning comes early, and after a hearty breakfast we’re on the road. Now the man who served dinner last night is driving my great uncle’s glassy black Cadillac past grassy slopes and rocky bluffs, on a road pointing toward the sky. The highway winds up the Mississippi valley toward its tributary where we plan to paddle.

The Beatles’ “Let It Be” is playing in the background. Our chauffeur drives as if racing the wind, his dark eyes tracking the black ribbon that twists through the valley. Driven by purpose, unshackled, as if he was no longer bound to his polished veneer that he was required to maintain around Unc. He chain smokes Chesterfields with the determination to deliver us to the river by 9:00 am.

Watching the landscape whip by, I was trying to forget the gnawing feeling that hit me in the gut a few weeks ago. I still can’t believe my stepfather is dead at a mere thirty-eight years old.

My eyes fixate on the land as we roll through the countryside; I’m grasping for euphoria from cloud shadows that race across the land, and the beams of light that descend upon hillsides through the thunderheads that stream across the sky. The bucolic scenery slips away as we eventually reach the slower cadence of the wild and scenic river.

The Upper Iowa is called a masterpiece; created in a flash of geologic time, it had been defined in a deluge, articulated through centuries. Delicate and perfect as a leaf, another one of nature’s miracles, like the greater driftless area that it is a part of—one piece in a grand mosaic. The landscape is a pristine habitat that supports an abundance of life: brook trout, bass, and a myriad of other creatures—songbirds, badgers, raptors, foxes and wolves, along with creatures and plant species uncommon to the otherwise surrounding Midwestern landscape. Such wildness makes me ponder both the majesty and cruelty of nature.

The river flows through the sleepy town of Dekora, about thirty-five miles as the crow flies from the put-in. Dekora, Iowa is home to Luther College and our river liaison—Dr. George Knutson, a Chemistry professor, and a fastidious fellow—as I learned when I called him to plan our trip. The good doctor is a plain and low-talking naturalist, a part-time outfitter. He offers guidance about the river and descriptions of rare trees, animals and unique geologic characteristics that he mentions while scribbling notes on our map.

“He’s quite the druid, that bloke,” Wallace whispers to us before driving off in a cloud of dust. Without my understanding of God, and with my deep love of the outdoors, I might have become a tree worshipper too, I think.

Knutson is lean and rugged and in a quiet sense very clear about his expectations and instruction. “You boys seem sturdy enough, but make no mistake, this is a wild river. What kind of experience do you have canoeing?” I thought we had covered that on the phone.

Where should I begin? I wonder why he doesn’t notice the canoe that practically grows out of my body, or whether he feels the sharpness of my gaze as a fellow modern-day voyageur. “We have paddled a lot sir. All over southern Ontario, rivers throughout the Midwest—Michigan and Illinois.” And as I ask, “any fish in your river?” I feel the shift the power.

“Lots of ‘em son. The fishing’s pretty darn good. In fact sometimes the bass jump right in your boat!” Now he’s selling it.

“You don’t say” I look at Wils and roll my eyes.

“Right into your boat, happens all the time.”

I had read about ancient speckled trout that still swam in the canyon waters of the Oneida River as they had for fortunate tribes who discovered this corner of the secret place that turned the glaciers away. I had not, however, read about any fearless, jumping bass.

After a forty-five minute ride in George’s pick-up truck, we are standing on the water’s edge, at a city park in the town of Lime Springs. We have our final discussion about fast water shoals, some water falls over dams that we’ll have to portage, and where to meet up when we finish. Now our trip begins.

It’s immediately apparent that this is no ordinary river. As we float past pastures, and farmhouses at the terminus of roads, I think about how fortunate I am, and I imagine Wils does too. We drift beyond the modern world, further and further from the usual controls on our lives. With each stroke, we begin to pick up speed. With the help of the current, the river carries us further into the past; past stretches distinguished by groves of coniferous trees otherwise only found in the forests of the northern Taiga.

We paddle and ride currents that cut through the canyon, beneath chimney rock formations and limestone cliffs some four hundred feet high. The wind stirs the trees. The river’s scale is smaller than the endless waters of Ontario but it has its own power. This basin a mere fractal of the whole driftless place: a pocket canyon; a sanctuary; a secret garden. In this haven, I found myself able to ask the question lingering on my lips: God please help me understand why he had to die, I pray silently to myself as the current carries us along.

We float and paddle. And as we drift, we crane our necks upwards to see the hawks and turkey-vultures patrol the skies. A Blue Heron lifts off ahead, then disappears around the next bend through a loamy mist that rises and dissipates before the face of chalky white bluffs. We hear the rat-tat-tat of a pileated woodpecker that draws our eyes to its bright, red-feathered head, illuminated between branches framed by light-green leaves touched by the sun. We paddle on.

Our goal is to finish this trip fast in order prove our skill, but mile after mile the river pulls us deeper into its spell. We are lost in the timelessness of a basin formed by the torrent of an ice-bound lake released upon the land. I imagine the surge of frigid waters that had cut and carved and carried away large portions of the earth.

After several hours, we near a place we don’t fully understand. It is an unexpected niche within this unusual ecosystem, like those more typically found at the edge of glaciers across the planet—not in a canyon in eastern Iowa. These patches of microclimates are rare small islands that appear upon algific talus slopes at the bottoms of north facing cliffs and covered in ferns and mosses. Within their delicate ecologies, I had read: near to the ground, temperatures are modulated by subterranean cave ice. Warmer in the winter and cooler in the summer.

The further we travel through the river’s basin, the more convinced we are that we have discovered this place for the first time. A mysterious place once hidden by surrounding mountains of ice. A place of rest, protected from harsher forces. Another kingdom. A bubble. A drop of water on a leaf.

Unc had referred to Galena and its surrounding countryside as a sanctuary. I understood what he meant. This place was sacred. And like Canada’s wilds, God’s presence is here, again, unmistakable to me. I realize God had not never left. In my disappointment and anger—in my disbelief, I had turned from Him. I had tried to outrun God.

In the middle of the river we step from our canoes into the shallow water atop a gravel bar. Here, as if standing on the water, we spin in slow motion amidst the three hundred and sixty degree wonderment. I continue to turn, looking up at the sky I attempt to breathe it all in. God had never left!

“Jubie, this place is incredible!”

“Yeah, I know.” My words are carried on the wind. My thoughts too. We return to our boat and continue down river alongside towering bluffs plastered with clusters of mud nest, each with its own opening. Our presence on the water swiftly detected, then followed by a cacophony of squeaks and squawks as small birds grate out their warnings.