Fifty years ago, when the unexpected happened, I didn’t know where to turn. “You can’t outrun God,” the priest had said—turns out he was right.

My family moved to the Midwest without my father when I was seven. At nine, I was fortunate to be introduced to the town of Galena by my great uncle. It was a different kind of place—a place of great surprises.

Our visits always involved exploring. Sometimes past cemetery park, we would walk down hundreds of sidewalk-stair-steps to explore the old commercial district—where the past came alive again. I welcomed the change of scenery: rolling hills, high bluffs and the mansions on cliffs, above the old town center that curved along the banks of the Galena River. These sights, imprinted in my memory, were reminders of a golden age.

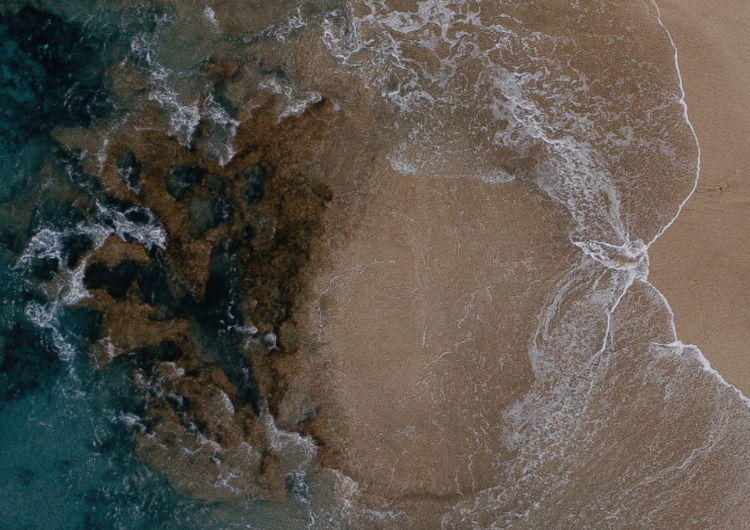

Exploring the countryside with siblings and friends, we took delight in the shadows of trees where we were enlisted to pick morel mushrooms that would be sautéed in butter and wine. When we picnicked, sometimes it was at The Rock—my great uncle’s treasured haven. It had been known as the Table Rock by the locals, and from the top of its bluff, we would stare for miles out across the Mississippi floodplain.

After feasting on sandwiches and pie, released again to wander the countryside, sometimes we would squeeze into crevasses cut into the bluffs: cave-like places, laced with rattlesnake shelter and the myriad lairs of mammals.

Our trips to Galena were always filled with delight, a stark contrast to the confusing world back home without my father.

In 1969, my mother remarried. We found ourselves welcoming an intriguing and cool guy named John into the fold, bringing three kids of his own. Our family turned into an amalgamation—something like the Brady Bunch. He became my long awaited savior; full of selfless care, helping me turn my life around. The process had already started in the Northwoods where I had almost lost my life to a whirlpool and had been baptized by the undertow. His part, however, the wilderness could not accomplish. He was a brilliant engineer who taught me the discipline of mathematics and analytical thinking, igniting the part of my brain I hadn’t yet exercised. And he taught me how to play Poker.

By 1970 I had spent four summers at camp, half the time out on canoe trips, paddling millions of strokes, trudging countless portages, and traveling nearly two thousand miles through the boreal forest by canoe and on foot. In this great expanse of meaning and learning, I no longer doubted who I was or worried about the trajectory of my life. And then the unthinkable…

At the end of that summer, my feet were knocked out from under me and my soul was crushed.

When he and my mom had seen me off at the beginning of the summer, we hugged, and my Mom said, “Make sure you bathe every day, and brush your teeth!” John had chuckled to himself; He knew how to let me go in ways she had not. “Have fun,” he said. “Remember what I said about doing your best.”

Those were the last words he ever spoke to me.

I first learned my thirty-eight year old stepfather was lying in a coma when he hadn’t been able to greet me upon my return from camp. That first day back was the first time I recall seriously bargaining with God. Sobbing under the waterfall of my grandparents’ guest room shower, I offered my life for his. Then I waited, and I prayed. And when I went to see him tangled in a jumble of wires and tubes, nothing happened but the dirge of the respirator—a harbinger.

A few days later, my mother arrived home, her hair a mess as she delivered the final blow. “He’s gone,” she said upon returning from the hospital, hollowed out, having aged countless years over those few days. That was when death burst through the wall of my life, sucked the breath out of John and tried to shake the life out of me.

I had done my best! But John was gone before I could tell him.

Amidst the unconscionable injustice, confusion descended like a poisonous fog. In my anger and disbelief, I turned from God. This might have happened anyway for a neuro-atypical teenager in the 1970s but my faith had been shattered. I had to escape from my hell—but I didn’t know how.